Hashavas Aveidah: 168 Missing Years found with Simanim!

A Critique of the Popular Revision of Alexander Hool

Note: The issue of the discrepancy between the Seder Olam chronology and the conventional chronology is not a new one. The challenge was discussed as far back as Saadiah Gaon, and there have been a plethora of Jewish responses. This post was submitted by the reader Yossi Kenner to critique a response commonly referenced in the contemporary frum world. To the best of my knowledge, this is one of the only responses that attempts to engage in the available historical evidence and defend the Seder Olam chronology, so a critique on this response is rather useful.

However, this post does not engage in the discussion surrounding the theological ramifications of this challenge. Many Orthodox Jews do not consider accepting the conventional chronology as a theological issue. Even in the Chareidi world Rabbi Shimon Schwab famously stated that Chazal purposely changed the history (although according to some sources he may have recanted). Among those that do consider it an issue, some of the issues discussed are Rabbinic fallibility, interpretation of the relevant passages of Daniel, and the possible gap in the Mesorah and its reliability. Each of these questions are important discussions in their own right, but that is not the focus of this post. Instead this post focuses purely on the evidence raised by Alexander Hool and the historical arguments he raises from them.

-Simon Furst

There is a long established controversy regarding how long the second temple stood for. Most orthodox Jews with a Yeshiva education believe it stood for 420 years; however, mainstream historians would argue it lasted for about 585 years. This controversy has been known as the Missing Years of Jewish History.1

Many have tried to advance arguments in favor of the oral histories transmitted by the Jewish sages. Some have theorized general solutions to shorten the Persian era, such as appealing to the possibility of coregencies and throne names, but few have seriously engaged in the historical data to see if their theoretical solutions can actually work. However, in 2014, Rabbi Alexander Hool published a book on the subject called The Challenge of Jewish History, in which he does engage in the primary sources of history.2 So let’s examine his arguments, and see if they hold water after all.34

The Foundation of the Conventional Chronology

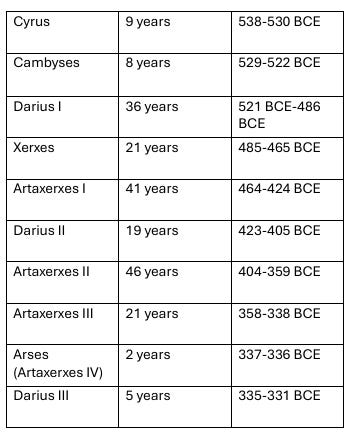

In chapter 3, Hool lays out quite a compelling list of diverse and independent historical sources for the conventional chronology. There are Greek historians like Herodotus and Thucydides from the 5th century BCE, and Xenophon from the 4th century BCE. We also have later authors like Diodorus (1st century BCE) and Plutarch (1st-2nd century CE) who cover the history of Alexander the Great and his conquest of the Persian Empire. Their histories make mention of the Persian kings, and put them in a general timeframe. Added to that, we have the writings of various other Greek authors like Plato, Aristotle, and Aeschylus, who also give us more chronological and historical data. There is also Manetho, the well-known Hellenistic Egyptian historian, who recorded the Persian kings who ruled over Egypt. We also have royal inscriptions from the Persians, which give us genealogies of the kings, as well as some biographical and historical information from their times. We also have papyri, ostraca, and many clay tablets, that record business transactions dated by day, month, and year of the king’s reign. We also have dated accounts of the of celestial bodies and lunar eclipses from the Babylonian astronomers, known as the astronomical diaries. With our modern knowledge of astrophysics, and with the help of computer programs, we can calculate how many years in the past these observations were made. Putting all this together, modern historians have managed to develop a precise timeline for this period of history. In the chart below, we can see the dates for the Persian monarchs who ruled over Babylon according to the conventional chronology.5

1st Revision: Thirteen “extra” years of the Greek era

First, Hool attempts to reduce the length of the Hellenistic period by thirteen years in an effort to shorten the Greek era in line with the rabbinic chronology.6 He starts with the discrepancies between the Uruk Kings List and conventional chronology based off the Saros Canon and the Babylonian Kings List.7 The first discrepancy is over Alexander the Great’s reign: the UKL says was seven years, while the Saros Canon says he ruled for eight years. The second discrepancy is over the reign of Seleucus I: the UKL says thirty-one years, which would imply that he died in his 32nd year, but the BKL says he died in month VI of “year 31” (Seleucid era8). The third discrepancy is the reign of Antiochus I: the UKL says twenty-two years, while the BKL says twenty. Hool admits they seem to be minor discrepancies, and indeed they are just that; a simple solution to the problem is to assume that the UKL has a few scribal errors or miscalculations. Especially in regards to the reign of Antiochus I, we know the UKL is inaccurate because the astronomical diaries and commercial documents both corroborate the BKL, as we see that even Hool writes in the book:

“The earliest cuneiform tablet dated to the reign of Seleucus II is a tablet from Uruk (BRM 1117) [BRM II 17] dated 22/03/67. This would imply that the previous king died sometime in the previous year, Year 66. The Babylonian King List reports the death of Antiochus II in Year 66. This is echoed in the astronomical diary for the Year 66 (BM41633) which states ‘Regular observations from Nisanu (I) to Ululu (VI), Antiochus king; from Abu (V) to Ululu (VI), Seleucus, his son, king.’” (page 39)

Since both kings lists agree Antiochus II ruled for 15 years (51-66 SE), and that Seleucus I ruled at least part of 31 SE, there is only 20 years maximum available for Antiochus I, which fits with the BKL and cannot work with the UKL.

There is also an interesting phenomenon we see with the business records from Babylon.9 Starting in 18 SE, Antiochus I became a coregent with his father Seleucus I. We know this because the documents state “Year x, Seleucus and Antiochus, kings.” But suddenly, a switch happens in a document from 12/II/32 SE (Erm 15646) where it dates to Antiochus alone. However, later texts from the same year start dating to “Antiochus and Seleucus, kings.”10 This has been identified as a son of Antiochus I, mentioned in the Antiochus Cylinder.11 In BM 55437, it says “year 46, Antiochus and his sons, Seleucus and Antiochus being kings,” and after that, we start seeing texts with only “Antiochus and Antiochus his son, kings.” This continues to 51 SE. But in middle of that year, we start getting texts with only one Antiochus being mentioned. Thus, the beginning to end of Antiochus I reign appears to be 31-51 SE, just like the BKL. Based on this evidence, it seems most reasonable to treat the other discrepancies as being scribal errors on part of the UKL.

However, Hool doesn’t want to go down this route, and instead takes the UKL as being correct and the BKL and the astronomical diaries as being inaccurate.12 Thus, he removes a year from Alexander, assuming he conquered Babylon in his 7th year as king of Macedonia,13 adds a year for Seleucus I, and another two more for Antiochus I. However, that only gets him a total of two years longer, which is hardly an improvement. Therefore, Hool claims there was a coregency between Antiochus II and Seleucus II for fifteen years, thus removing a total of thirteen years from conventional history. Based on this view, Alexander conquered Babylon in 318 BCE, Phillip began his rule in 311 BCE, Antigonus the General in 305 BCE, Seleucus I in 299 BCE, Antiochus I in 268 BCE, and Antiochus II together with Seleucus II in 246 BCE. Hool says that there is “circumstantial evidence” for a coregency by the existence of a second royal city called “Seleucia of Euphrates.” However, the fact that there may have been a second royal city, similar to how the Persians had Susa and Persepolis as two royal cities, isn’t strong evidence of a coregency. A royal city just means more officials, not necessarily more kings.

Hool also claims that his revision is supported by an astronomical diary (BM 34616), which based off the sightings described within the text indicates a date of 302 BCE, but the text is dated to “year 4.” Hool says this refers to 4th year of Antigonus the General who ruled during the “kingless period” mentioned in the BKL. However, the BKL itself says Seleucus I began his 1st year as a king (as opposed to being a satrap) in 7 SE (305 BCE), and thus his 4th year would be 302 BCE according to the conventional chronology.14

Aside from that, there is no written evidence for this alleged coregency. It’s not mentioned in the BKL, UKL, astronomical diaries, Saros Canon, Greek historiography, second temple Jewish text, or in the early rabbinic literature. What’s worse is that the business documents seem to refute this idea as well. As we have already seen, documents dated during a coregency have both rulers mentioned. But Antiochus II is clearly seen ruling alone up to 66 SE, while Seleucus II is ruling from 67-86 SE.15 Therefore, it’s safe to say Hool’s desperately needed coregency is baseless.

2nd Revision: 155 “extra” years from the Persian era

We move on to the main revision, where Hool removes another 155 years from the conventional chronology from the Persian period. His main thesis is that Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire from Darius I, as opposed to Darius III, and ruled over it alone for three years. After that (314 BCE), Alexander allowed Xerxes to be his vassal, ruling over the Persian empire on his behalf. With the death of Alexander and the splintering of his empire, Hool says it’s possible that the Persians regained independence, and ruled contemporaneously with the Seleucids, Ptolemies, and Parthians, up to their last king, Darius III (164-159 BCE). To back this revision up, Hool provides us with several exhibits of evidence.

1) The Bible

Hool quotes the prophecy in Daniel 11:2-3 that there will only be four kings for Persia before the conquest of Alexander the Great. Following Hool’s thesis, this prophecy can be fulfilled (Cyrus, Cambyses, Bardiya the usurper, and Darius I). However, if we follow the conventional chronology, we would have way too many kings.

But prophecies and predictions of the future are not the same as historical records of the past, because sometimes prophecies are not fulfilled. Jeremiah 18:7-10 says that even if God makes a prophecy regarding a nation, he can always change His mind if the nation changes their moral character. So, perhaps Persia was supposed to have only four kings, but because the people did some sort of good deeds God granted them a longer duration.16 We should also point out that there is a well known Jewish tradition that Daniel is written cryptically, to conceal the date when the Messiah will come. So perhaps the number of kings is to be understood symbolically. Also, many religious scholars believe the four kings are mentioned only due to some sort of significance they played, and that Daniel doesn’t bother to mention all Persian kings.

From a secular critical-historical viewpoint, the book of Daniel was composed in the 2nd century BCE. The main reason for this view is that Daniel 11:40-12:3 indicates that the end times would happen right after the Seleucid king Antiochus IV is defeated, which everyone knows didn’t happen. Also, the many inaccuracies of Babylonian and Persian chronology found earlier in the book, together with the high degree of accuracy for the Seleucid and Ptolemaic wars described in chapter 11, is used by scholars to date when the text was composed. The author must have predated the death of Antiochus IV (in 164 BCE) to explain his failed prophecy; his knowledge of the Seleucid-Ptolemaic conflicts down to the time of Antiochus’ persecution of the Judeans (in v. 30-39) implies he postdated those events; and his inaccuracies regarding the Babylonian and Persian periods makes sense, since the author would have been centuries removed from that time.17 If so, Daniel 11:2-3 should also be viewed as a mistake made by a 2nd century BCE author.

It is interesting to note, that other parts of the Bible seem to have a longer Persian chronology. In Ezra, we have mention of Cyrus, Ahasuerus (identified as Xerxes),18 Artaxerxes, and Darius. In Nehemiah (12:8-22), we see another Darius who lived some six generations after the building of the Temple (most likely Darius II). Even Daniel 9:24-27 may be evidence of a longer chronology. If we interpret v. 26-27 to be predicting the persecutions of Antiochus IV after 62 sabbaticals (434 years) since Jerusalem was rebuilt, we would get a rather long chronology. Thus, for all the reasons cited above, the Bible isn’t a good argument for Hool’s revisions.

2) Jewish History

Hool says that besides for Seder Olam, the shorter rabbinic chronology “can be arrived at through six separate ways, a number of them intricately connected with the very fabric of Jewish history” (page 48, also see chapter 2.) However, most of the six sources are rabbinic texts that rely on Seder Olam. The rest are contemporary rabbinic texts from Judea, like the Mishnah and Tosefta, which probably depended on Seder Olam’s text and/or methodology. Thus, this isn’t a case of multiple independent sources, but a repetition of the same source, which itself is centuries removed from the period of time in question.

Seder Olam is attributed to Rabbi Yose Ben Chalafta (2nd century CE) and is quoted in several Talmudic texts. In chapters 28-30, we see how he reached his conclusion. He interpreted the Seventy Weeks prophecy (which is 490 years) in Daniel 9:24-27 to start at the destruction of the first temple and ends with the destruction of the second temple. Given Zachariah 1:12 says the temple wasn’t rebuilt for seventy years, we are left with only 420 years for the duration of the second temple. Because Rabbi Yose was aware that the Seleucid era started in 311 BCE, as well as the fact that Daniel 11:2-3 promised only four Persian kings, he specifically had to shorten the Persian period.

However, as we already explained, these literalistic readings of Daniel for historical purposes are highly problematic. Without checking the history books of their time, it is no wonder that Seder Olam would produce an erroneous chronology. Given the fact that most rabbis of that time didn’t study history, it’s no surprise that the sages of the Talmud relied on Seder Olam for chronological information, and after several centuries of reliance on it, it became a unanimous tradition. One can argue that the Christian belief that the Messiah’s death was predicted by Daniel (9:24-27) to happen the same year that Jesus was crucified, caused the Jewish people to be even more suspicious of the conventional chronology. In a similar vein, ever since the rise of polemics against the oral tradition, there was even greater reason to dogmatically teach that we have an unbroken chain of narration of those who passed down the oral laws from Moses to the present. Thus, Seder Olam’s chronology would be held with even greater esteem, to the point that those who are skeptical of it are deemed having at least one foot on heretical ground.

It is interesting to note that the Jewish historian Josephus, who predates Seder Olam, believed in a rather longer Persian chronology.19 So this idea that “Jewish history” unanimously held to a short Persian chronology is simply false.20 What we are dealing with is simply a popular, yet erroneous, chronological tradition from the rabbis that developed and was maintained for a host of bad reasons.

3) The Uruk King List

Hool points out that the reverse of the UKL has a Niddin-bel, followed by a Darius, and Alexander. Hool identifies Niddin-bel as Niddintu-bel of the Bihistun Inscription, who was a usurper to the throne of Darius I. However, the Darius of the UKL is said to rule for five years, while Darius I had at least thirty-six years to his reign. To solve the problem, Hool says that perhaps the text should be reconstructed to have read thirty-five, but also says, “if a construction to thirty-five cannot be made, it is evidently a scribal error which may have occurred when copying from unclear source material (page 51, note 71).” A reconstruction is not possible, since this section of the text is quite visible, and the numbers are placed within a column and there is a clear space between the “five” and the word “years.” Instead, we should view the mention of Niddin-bel as an error made by the scribe’s confusion between Darius I with Darius III.21

Hool also points out that the UKL doesn’t have the names of many Persian kings known to the conventional chronology. However, the most likely reason for this is because the bottom part of the list was broken off and lost. This would be consistent with the fact the tablet is missing parts of lines 12-14, which scholars have reconstructed as saying Cyrus, Cambyses, and Darius (I). So no, the UKL isn’t strong evidence for revising the chronology by over a century and a half.

4) The Cuneiform Text

BM 36613 BM 36613, also known as the Alexander and Artaxerxes Fragment,22 makes mention of a date during the reign of “Arses, son of Ochus, who is called Artaxerxes,” as well as people mourning for Alexander. Hool sees this as a contradiction because he assumes the text said Arses was present at the mourning ceremony. However, this interpretation is highly speculative, since we are missing quite a lot from the tablet. In fact, we don’t have the beginnings or ends for the lines of the text, and thus we don’t know how many words and sentences there were between the mentioning of Arses in line 6, and the mourning for Alexander in line 8; nor do we know the content of the missing texts, and thus we don’t know for certain if there was or wasn’t a contradiction to the conventional chronology. Professor van der Spek explains that the text was making a reference to an event during the reign of Artaxerxes IV, and then later talks about Alexander’s building activities. Another explanation is that the mentioning of Arses is a quotation of a letter that is read aloud in a broader narrative, and thus there is no chronological problem.

According to Hool, this Arses is really Xerxes. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that Xerxes was known by any of his contemporaries as Arses, the son of Ochus, or Artaxerxes. However, we do know that Artaxerxes IV was called Arses, and that his father, Artaxerxes III, was named Ochus.23 Indeed, this solution is just a cop-out that anyone can use to defend any chronology they want.

5) The Alexander Chronicle (BM 36304)

The Alexander Chronicle (BM 36304) speaks of the removal of Darius III by Alexander’s armies, and like the previous text, it is also damaged and has a lot of unreadable sentences. In the translation by Albert Kirk Grayson,24 Darius is called “the king of kings.” Hool says that Darius III was too weak of a ruler to use the title king of kings. Instead, he interprets this Darius to be talking about Darius I, who uses such a title in the Bihistun Inscription.

This argument is very strange, given the fact we have inscriptions from Darius I, Xerxes, Artaxerxes I, Darius II, Artaxerxes II, and Artaxerxes III where they use this as one of many standardized titles.25 We don’t have any royal inscriptions from the shorter reigns of Arses and Darius III. But from what we do have, its quite reasonable to assume that this title was also used by them.26

The text also makes mention of a festival to Bel, a Babylonian god. Hool claims that we would not expect the cult of Bel to survive 200 years of Persian domination, implying that persecution and assimilation would end this long standing religious tradition of Babylon. However, history tells us of many religious traditions which survived similar conditions. For example, the early Church was persecuted for centuries by the Roman empire, and still managed to survive.

Herodotus (1.178-183) makes mention of the temple of Bel, calling the deity “Zeus Belus.” He also makes mention of Xerxes carrying away a golden statue from the temple. Arrian (Anabasis of Alexander 7.16.5-17.5) says that when Alexander went to conquer Babylon, he wanted to rebuild the Temple of Bel that laid in ruins since the days of Xerxes. Diodorus (17.112) says that the Babylonians asked Alexander to rebuild the “tomb of Belus.” We also have several documents, (BM 87261 dated to 2nd year of Phillip III,27 321 BCE; HSM 893.5.17 dated to the 6th year of Alexander IV, 311 BCE; and Colombia 362 dated to his 10th year, 306 BCE)28 which refer to property of the god Bel. We have tablets (BCHP 5 6, also known as Antiochus I and Sin Temple Chronicle29 and the Ruin of Esagila Chronicle30 respectively) which makes mention of crown prince Antiochus (I) and worship of Bel. Pausanias (Guide to Greece 1.16.3) says that Seleucus I spared the sanctuary of Bel and allowed the Chaldeans to live there. We also have some later business records dated to 58 SE mentioning the “estate of Bel” (CT 49, 126.)31 Strabo (Geography 16.1.18) says that Antiochus the Great (III, 187 BCE) was killed when he tried to rob the “temple of Belus” somewhere in Persia. We know of the temple of Bel in Palmyra, in which inscriptions of dedications of statues from the 1st century BCE until 1st century CE.32 We also have a statement in the Babylonian Talmud (Avodah Zarah 11b) regarding the Babylonian Temple of Bel in the 3rd century CE.

“Rav Ḥanan bar Rav Ḥisda says that Rav says, and some say that it was Rav Ḥanan bar Rava who says that Rav says: There are five established temples of idol worship: the temple of Bel in Babylonia; the temple of Nebo in the city of Khursei; the temple of Tirata, which is located in the city of Mapag; Tzerifa, which is located in Ashkelon; and Nashra, which is located in Arabia.”

Rabbi Yaakov Emden (Haggahot Ya’avetz, ad loc.) explains that although Jeremiah 51:44 and other extra-biblical sources indicate the temple of Bel was destroyed in the days of Daniel, it was later rebuilt. So, as we can clearly see, the tradition of Bel worship continued for over a millennium. Yes, there is evidence that Xerxes was intolerant to the Babylonian temple of Bel, but in no way does it mean that Bel worship was successfully stomped out. We see many theophoric names with Bel being used in the Murashu archives from Nippur during the reigns of Darius II.33 The mention of Bel has no bearing on the chronology of the Persian era.

6) Cuneiform Evidence in Babylon

Hool points out that there is a massive decrease in cuneiform documents from Babylon, starting from the reign of Xerxes down to Darius III. He says that this is evidence that the Persians were weak, and that other entities, like the Seleucids, shared rule over the empire. However, this is an argument from silence, and is notoriously weak, since finding ancient documents isn’t always guaranteed.34 So, while there may be a decrease in documents, the fact that we still have some documents from Babylon indicates Persian rule continued, just as the conventional chronology claims.

7) Inscriptions and Documents from Persia

Hool argues that there is little evidence for the Seleucid rule in Persia. However, there is evidence from excavations in Susa35 and even as far as Ai-khanoum36 (modern day Afghanistan) of Seleucid rule. From Bactria, we have several documents dated from Artaxerxes III, Darius III, Alexander the Great, and even a possible reference to Satrap Bessus, also known as Artaxerxes V.37 So again, lack of evidence isn’t evidence of lack, and the ounce of evidence is heavier than the pound of Hool’s speculations.

8) Papyri and Inscriptions from Egypt

Hool also mentions that we have very few Persian inscriptions and documents from Lower Egypt after the reign of Darius I. Therefore, Hool believes that Xerxes and his descendants ruled only in Upper Egypt, while the Ptolemaic dynasty controlled Lower Egypt. Again, this too relies on a lack of evidence being evidence of lack, as well as ignoring the ounce of evidence for the pound of speculation. We do have some documentation, for example, the letters of Arsama, who was the satrap of Egypt during the time of Darius II.38 In one letter (TADAE A6.10), Arsama makes reference to a revolt, and writes “to Nakhthor the official who is in the lower of Egypt” (line 11). He demands he fight back against a revolt, and be diligent in protecting his property. This implies that the Persians still had a significant military force in Lower Egypt. In the Elephantine Papyri, we have a letter (A6.1) addressed to Arsama by several of his officials. On the external address of the text, there may be reference to a location in Lower Egypt as a province of some of his officials. In Saqqara, an Aramaic inscription dated to the “4th year of Xerxes” has been found.39 Also, there is a text dated to the 15th year of Xerxes from Memphis, Lower Egypt.40 So while there may be a reduction in evidence, there is still enough to refute Hool’s suggestions. We also have some papyri found at Elephantine that date to the time of Ptolemy I-III,41 which would overlap with Hool’s revised chronology of the reigns of Xerxes-Darius II.42 It’s not likely that the Persians and Ptolemaic rulers both ruled over Elephantine, thus the Elephantine Papyri clearly suggests that the conventional chronology is correct.

9) The Gap between Darius I and Xerxes

Hool claims that there is clear evidence for a gap of three years between Darius I and Xerxes. His first argument for this is are documents that date to month XII of Darius I’s 36th year, and other documents that date to month VIII of Xerxes’ accession year. This could be a result of either a coregency between the two, or a gap. Given the fact that an inscription from Xerxes43 says he became king only after his father Darius “went away from the throne” it can only be explained by a gap. However, Stefan Zawadski argued that perhaps these scribes were waiting for an official accession ceremony for Xerxes before dating the documents by his reign.44

Hool brings up the nineteen-year cycle of intercalary months, in which years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, & 19, a thirteenth month was added to have the lunar months catch up with the solar year. It appears that Darius’ 35th year was the 11th leap year of the cycle, while Xerxes’ 2nd year was the 17th. Therefore, Hool argues that there must have been a three year gap, caused by Alexander the Great’s conquest of Babylon. But this cannot be done, since we have numerous astronomical diaries that independently date the reigns of the kings and the celestial cycles, and there is no room for such a gap. In light of that, it would only seem fair to conclude that the Babylonian priests, for some reason,45 decided to change the leap year sequences for that year. In fact, some scholars believe there were other times the leap year sequence was changed. For example, Mathieu Ossendrijver argues that the 8th year of Xerxes and the 20th year of Artaxerxes II were leap years that deviated from the patterns as well.46

Hool also points to a relief depicting Darius I with two attendants. One of them has an inscription saying “Xerxes, son of Darius the king of Achaemenid.” Hool argues that the statue dates after the death of Darius, and that because the inscription doesn’t give a royal title to Xerxes, it must have been written before he became king. However, there is no good reason to date this relief after the death of Darius. Instead, one can easily conclude this inscription must have been made during the reign of Darius, thus explaining the absence of royal titles for Xerxes.

10) Synchronization with Ancient Egyptian Papyri

Hool brings up the Elephantine Temple Papyri as evidence of a synchronism between Darius II and a high priest named Yehohanan. Hool identifies this man with Yochanan Kohen Gadol from the rabbinic tradition, who served as high priest for eighty years after the service of Simon the Just.47 Simon is said to have met with Alexander the Great, which in turn would imply that Yochanan/Yehohanan and Darius II postdate Alexander, which would be in line with Hool’s chronology. However, there was an earlier priest with the same name, mentioned in Nehemiah 12:22-23, which fits very well with the conventional chronology. The same papyri also mentions the children of Sanballat, the governor of Samaria, who also appears in the Book of Nehemiah (2:19-20, 3:33-4:2, 6:1-9, 13:28). Nehemiah lived during the 32nd year of Artaxerxes (13:6), and if we assume like most scholars that this is Artaxerxes I, we just need to count twenty-six more years to reach the 17th year of Darius II. Indeed, Nehemiah 12:22 says that the genealogies of the Levites during the lifetime of Yohanan was recorded during the reign of a “Darius the Persian” that postdated Artaxerxes. The Book of Nehemiah (12:11; 22) also makes mention of the priest Jaddua. It is interesting to note, that in Josephus’ version of Alexander the Great meeting the high priest in Jerusalem, he identifies him as Jaddua instead of Simon the Just.48 This further demonstrates that the rabbinic tradition is a development of older traditions, which was modified to fit their shortened chronology.49

11) The Elephantine Papyri

Hool brings down around twenty legal documents of the Elephantine papyri collection which are double-dated using the Babylonian and Egyptian calendars. Many of the dates are off by a day, and some even by two days. Sacha Stern has proposed that the reason for the conflicting dates is simple: Elephantine was far away from Babylon, and perhaps delays in notifications of the official date of the new moon didn’t reach them in time, so they estimated a date for the Babylonian calendar.50 Bezalel Porten is quoted as explaining most of the discrepancies to scribes writing at night, when the Babylonian day began, but while the Egyptian day would only start in the morning.

However, Hool says that these solutions are strained, and instead he suggests we shift the time down using his revised chronological scheme, which would make an even bigger discrepancy of 42 days or more! To solve this problem, Hool makes another assumption that the Egyptian calendar was changed, where the new year was announced around 42 days earlier than expected. With that all worked out, Hool manages to get almost all of the dates matching, besides for three of them, which he attributes to scribes writing them at night.

But this is simply conjecture. There is no written evidence of the Egyptians changing their calendar like Hool suggests. And as we have already seen, there is no evidence from the primary sources for this lower chronology. But even if we grant these assumptions without evidence, Hool’s dates are still off, and require a third assumption that those documents were written during the night. While it is always possible Hool is correct, his reliance on these three assumptions looks rather weak compared to Stern’s explanation.

Another interesting fact, Ptolemy III tried to add an additional day every 4th year to the calendar. We know about this because he had to write public decrees about it, and we have several copies that survived.51 We also know that the people never accepted the reform by Ptolemy III, and it took until 26-25 BCE for this reform to actually get accepted by the masses,52 despite the fact it was a reasonable reform, attempting to account for the quarter day of the solar year. If this reform was rejected by the public, I highly doubt Hool’s hypothetical reform, which had no apparent astronomical purpose, would have been accepted by the same population.

In conclusion: none of these arguments pass the sniff test to lower the accepted chronology. While it is true that there are some ambiguity regarding some elements of the history, none of them raise doubt to the standard chronology in any meaningful way.

Evidence of an International Conspiracy?

Even if we were to give Hool his interpretation of these data points, he still would need to explain the extensive contemporary historiography of the Greeks, as well as the astronomical diaries which would not allow for his revisions. That is why he claims that there was a massive conspiracy across the entire Hellenistic world to falsify the historical record, and it went undetected for over 2000 years! But lest the reader think I am misinterpreting Hool, I shall let his words speak for themselves.

“Evidently, some time after the facts, a new distortion of historical documentation was introduced in an attempt rewrite history, shifting the whole of the Persian era back in time, making its demise coincide with the rise of Alexander the Great. In reality, the Persians had a mini-empire alongside the Greeks. In this “altered history,” Alexander and his successors ruled over Persia completely.

As we will see, there are many indications of an elaborately planned and mathematically calculated deception, involving the manipulation of the histories of Persia, Greece, and Egypt as well as the adaptation of the astronomical diaries. This “alteration” of the dating of previous events took place sometime after the fall of the Persian Empire in 160 B.C.E.

The necessary steps taken appear to be as follows:

To create or adapt works of contemporary historians of the latter Persian period in order to portray this period as coming before the onset of the Greek era.

To fabricate documentation of Alexander the Great defeating Darius III as opposed to Darius I.

To destroy archives of astronomical diaries from the period prior to the Greek era and amend the remaining ones to the latter Persian rulers.

To add thirteen years to the Greek era in order to allow the shifting of the Persian era by a multiple of nineteen years; and to reform the Egyptian calendar.” (pages 89-90).

This is beyond ridiculous. How on earth would such a complex forgery be accomplished? We have to remember, that even according to Hool’s view of history, we are talking not about one empire controlled by one government, but by at least four different kingdoms, each of them engaging in a series of wars over territory and resources, suddenly decided to put aside their differences and hatred for one another, agree on a fake history, fund and coordinate a massive international conspiracy, while ensuring that no one notices that the history books of last year were suddenly changed. This is extremely unlikely to have happen, and if someone actually attempted this, we would expect to see a swift correction done once these rulers lose power. It is extremely difficult to uproot a historical tradition that already entered the record.

But for the sake of the argument, even if we grant this ludicrous idea, what would motivate someone with such abilities to change the entire historical record? Hool provides several hypothetical reasons for the motivation. One assumption is that the Greeks feared people would see that the prophecies of Daniel are coming true and that they were next in line to be defeated. So, in an effort to calm the public, they decided to change history to show that the book of Daniel is unreliable. This assumption isn’t a very plausible explanation at all. For starters, an average person of the 2nd century BCE didn’t study the Bible, let alone the lesser known Book of Daniel. And for the evidence we do have of pagan philosophers reading the book of Daniel, like Porphyry of Tyre (3rd century CE), it seems they simply claimed it was written during the Maccabean revolt. So, if there actually was a need to discredit the book of Daniel, there was no need to destroy thousands of documents from around the world, all one needed to do is spread the claim that it was a 2nd century BCE book. But even if that wasn’t an option, why couldn’t the authorities simply ban the book of Daniel? Wouldn’t that be enough to destroy the public knowledge of the doomsday predictions?

Another speculation Hool offers is that the Greek conspirators wanted to hide the fact that the Persians ruled alongside their kingdoms because they were somehow embarrassed by it. But what’s so embarrassing about the Persian people ruling along side the Ptolemaic and Seleucid kingdoms? It’s not a claim that belittles anyone anymore than the fact Alexander the Great died at a young age, and that his empire was split up. If the Greeks were in the business of manipulating the history books, why didn’t they remove these equally “embarrassing” facts about Alexander? Strangely, the Greeks didn’t cover up the fact that the Parthians took control of Seleucid territory in the 3rd century BCE, so why would we expect a cover-up over the fact that the Persians, who were given autonomy by Alexander, also ruled alongside the other kingdoms? Also, why would we suspect the Ptolemaic kings to collude with this cover-up? They don’t have any goal in hiding embarrassing facts about their enemies.

Another possible motive given is that the Greeks were trying to cover-up the fact that Greek philosophy was really culturally appropriated from others. This too, doesn’t pass the sniff test. If the Greeks borrowed wisdom from an earlier non-Greek, all they would need to do is invent fables of a legendary Greek teacher who taught wisdom to the philosophers, or they could claim that these non-Greeks had Greek origins. It would be cheaper and way more effective in convincing the masses than any international conspiracy of revising historical traditions that were already in circulation for centuries.

In all, we see no evidence of a forgery, we see no motive for a forgery, and we don’t have any suspects with the capabilities to carry out a forgery.

Additional Problems with the revisions

One of the biggest problems with Hool’s revision, is even if we were to grant him all his conspiracy theories, he would still have problems explaining some business documents found near Jericho known as the Samaria Papyri. In one of the documents (WDSP 1), it says “On the 20th of Adar, the year 2, the accession year of [D]arius, the king, in Samar[ia].”53 It was the standard way of dating documents from the accession years to include the years of the previous king, without mentioning him by name. Thus in the Elephantine Papyri (TAD B2.2) it says: “year 21, the accession year, when Artaxerxes the king sat on his throne.” Given that’s the case, the two year reign can only belong to Arses (Artaxerxes IV) and thus this Darius must be Darius III. The only problem is, Hool has his accession dated to 164 BCE, the time of the Maccabees! Obviously the Persians were not in control of Judea and Samaria at the time of Antiochus IV, as the Jewish sources of I & II Maccabees clearly demonstrates.

What’s strange is that Hool didn’t even notice this, despite the fact he quotes it in his book!54 So I sent him an email with this question. He first responded with the claim that the text was written outside of Israel. So I sent him a picture of the Aramaic text as well as the English translation, and asked why it said “king in Samaria.” Finally, he admitted he was wrong, and said:

“I now believe that the text is referring to the accession year of Darius I when he became king over the whole empire which indeed took place in his second year after he finally quelled all the rebellions mentioned in the Behistun inscription.”

I tried to tell him that the standard way of dating the text implies this is Darius III. I challenged his claim that all rebellions were quelled in the 2nd year, since the Behistun Inscription clearly says that rebellion was still happening in his 3rd year. I also challenged him to produce a similar text with a similar dating formula from the many documents from the reign of Darius I. But to no avail, he used every intellectual escape hatch not to interpret this text in the straightforward manner he previously did.

Beyond this, the Letter of Aristeas (dated to the 3rd- 1st century BCE), Josephus (Antiquities 12.1.1), and even an Idumean inscribed ostraca55, further demonstrate the control over Judea by Ptolemy I & II during the time when Hool thinks Darius II controlled the same territory (based on the Elephantine Temple Papyri.)56 Are we to believe that these Judean/Jewish sources were also forged? Or are we to believe that there was some sort of joint rule between the Ptolemies and the Persians? Furthermore, the Book of Daniel makes no mention of the Persians controlling Israel during the Seleucids and Ptolemaic wars, nor does Seder Olam or any other rabbinic texts. If Hool was correct, would we not expect they “uncorrupted” Jewish tradition to make mention of this? How about the Romans, didn’t they realize that the Greeks were falsifying the historical record? Didn’t they already have copies of Greek writers enter their libraries? How did they not blow the cover of this fake history? Hool’s model of history is obviously absurd, and despite his wonderful intelligence and writing abilities, he is presenting a bunch of nonsense to his audience.

Conclusion

Rabbi Hool is not the first person to abuse the historical literature for his agenda, nor will he be the last. However, it is quite difficult to defend the Seder Olam chronology with the data given. I know some people who think this is not a serious challenge to Orthodox Judaism, and I know some who think it is. Personally, I believe this is one of the best demonstrations of the fallibility of religious dogma, and thus we should all be open to the critical-historical method in the study of religion.

I have tried, so far unsuccessfully, to find an online or PDF version of the book to make it accessible to all. If anyone is aware of such a thing I would appreciate if you can leave a comment or send me an email at simonfurst7@gmail.com. -S.F.

For two reviews on his book, see this review from A. L. Englander, and this anonymous review.

All references in this paper of Hool’s book are based on the second edition from Mosaica Press, 2015.

This chart can be found in Hool’s book at the beginning of chapter 3. Obviously there is a margin of error of a couple of months, as well as a few usurpers who ruled for less than a year in between several kings. But in all, it is a fair and useful representation of chronology.

Babylonian Talmud, Avodah Zarah 9a.

Both the UKL and BKL can be found on livius.org. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/uruk-king-list/ and https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/babylonian-king-list-of-the-hellenistic-period/

Also known as Minyan Shtarot in the Jewish tradition. For the development of this dating system, see https://www.livius.org/articles/concept/seleucid-era/

For a sample of these texts, see http://attalus.org/docs/cuneiform.html

There is a later document dated to 8/X/32 SE dated to “Seleucus and Antiochus,” but it’s most likely a scribal error.

Available here https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/antiochus cylinder/

Hool makes the claim that because the UKL ends with the reign of Seleucus II it must have been written very close to his death, implying that it is more reliable than the other documents due to its age. However, as we will later discuss, we are missing the end of the list, and therefore it can very likely be that the text is actually younger.

Hool also claims that we lack documents from the 7th year of Alexander, because it was his accession year. However, this is an argument from silence, which demonstrates nothing on its own, which is worthless because Hool himself says that the astronomical tablet LBAT 1397 dates the 7th year.

Hool knows of this interpretation, but argues that because the business records count from Seleucus I as being king starting in 1 SE, there is no way that a different scribe writing the astronomical diaries would use an alternative dating system found in the BKL. But this line of logic is obviously flawed, how can one rule out a that no one used a similar dating like the BKL in this text?

Hool claims that they only dated their documents by Seleucus II because they hated Antiochus II, but that is just a lame excuse, given the fact his coregency is baseless to begin with.

The same explanation can be said regarding the prophecy of Daniel’s Seventy Weeks. Perhaps the Jewish people did some sort of sin that caused some delays and gaps between the timeline outlined in Daniel 9:24 27.

For more, see John J. Collins’ Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel. Fortress Press, 1994.

For the evidence of this identification see https://thetorah.com/article/if-achashverosh-is-xerxes-is-esther his-wife-amestris. In chapters 16 of his book, Hool argues that Ahasuerus is really Cambyses, but his arguments are rather weak in light of the strong linguistic connections between Xerxes and Ahasuerus.

See Antiquities of the Jews Book 11. Also see ibid 12.7.6 and Jewish Wars 6.4.8

Clement of Alexandria (The Stromata 1.21) quotes a Hellenistic Jewish chronicler, Demetrius (3rd century BCE), with a similar long chronology. It is interesting to note, that both Josephus, Demetrius, and the critical historical interpretation of Daniel 9:24-27, seem to overextend the chronology by around 60-70 years. I have not found a suitable explanation for how these errors were made.

Or, we can drop the assumption that Niddin-bel is the same as Niddintu-bel, and have him be a new usurper.

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/bchp-4-alexander-and artaxerxes-fragment/

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica 17.5.3

Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. Eisenbrauns, 1975, pages 112-113

All texts can be found here https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/ (Inscriptions XV; A1Pa; D2Ha; A2Ha; A3Pa.)

Hool admits in a footnote that an alternative translation says “the king went” in place of “the king of kings.” The new translation is available here: https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles content/bchp-1-alexander-chronicle/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/

https://www.academia.edu/23452292/Late_Achaemenid_Early_Macedonian_and_Early_Seleucid_Records_

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/bchp-5-antiochus-i-and-sintemple-chronicle/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/bchp-6-ruin-of-esagilachronicle/

https://www.academia.edu/954692/Agricultural_Management_Tax_Farming_and_Banking_Aspects_of_Entrepreneurial_Activity_in_Babylonia_in_the_Late_Achaemenid_and_Hellenistic_Periods

Javier Teixidor. The Pantheon of Palmyra. Brill, 1979, pages 1-3.

Albert T. Clay Business Documents of the Murashû Sons of Nippur, Dated in the Reign of Darius II (424-404 B.C.) University of Pennsylvania, 1904, page 9.

As to the reason why we don’t have as much documentation from the later periods, perhaps it is because the people started to use papyri and leather instead of clay tablets, which gets damaged and destroyed by the elements way quicker than baked clay.

https://www.livius.org/articles/place/susa/ “Seleucid, Parthian, Sasanian Age.”

Laurianne Martinez-Sève. “The Spatial Organization of Ai Khanoum, a Greek City in Afghanistan.” American Journal of Archaeology. Volume 118, Number 2, April 2014.

See here, https://www.khalilicollections.org/all-collections/aramaic-documents/.

Christopher J. Tulpin and John Ma. Aršāma and his World: The Bodleian Letters in Context, Volume I: The Bodleian Letters. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Pierre Briant. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns, 2002, page 964.

Bezalel Porten. “The Calendar of Aramaic Texts from Achaemenid and Ptolemaic Egypt” in Irano-Judaica II. Ben Zvi Institute, 1990, page 29.

Bezalel Porten. The Elephantine Papyri in English : Three Millennia of Cross-Cultural Continuity and Change. E. J. Brill, 1996. Documents C31-32 and D2-7.

While Hool doesn’t explain how he revises the Ptolemaic chronology, it’s a safe bet he would propose some sort of coregency to remove only thirteen years, just like he did for the Seleucids.

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/xpf/

Stefan Zawadski. “The date of the death of Darius I and the recognition of Xerxes in Babylonia” Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 1992-49.

It could be that the Babylonian revolt during the 2nd year of Xerxes caused the change due to some political instability.

Mathieu Ossendrijver. “Babylonian Scholarship and the Calendar During the Reign of Xerxes” in Xerxes and Babylonia: The Cuneiform Evidence. Peeters, 2018, pages 141-146.

Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 9a and 69a.

Antiquities of the Jews 11.8.4

It’s also fair to point out that Josephus doesn’t seem to know that there was any other king after Darius II (Antiquities 11.7.2), and thus he puts Jaddua and his contemporaries very close to Alexander's conquest of Judea.

Sacha Stern. “The Babylonian Calendar at Elephantine.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 130, 2000, pages 159–171.

http://attalus.org/egypt/canopus_decree.html

https://www.instonebrewer.com/TyndaleSites/Egypt/ptolemies/chron/egyptian/chron_eg_cal.htm

Douglas M. Gropp, et al. Discoveries in the Judean Desert: XXVIII. Clarendon Press, 2001, page 34.

Pages 50-51.

Bezalel Porten and Ada Yardeni Textbook of Aramaic Ostraca from Idumea: Volume 3. Eisenbrauns, 2018. Pages 184-185.

Not only Darius II, but Xerxes according to Esther 1:1 and Ezra 4:6; Artaxerxes I according to the Ezra 4:7, 7:21, 25, 8:22, 36, and Nehemiah 2:7-9, 3:7, 13:6. Hool’s theory also involves the Seleucid empire controlling much of Babylon and Syria, yet we are told by these passages that the territory “beyond the river” was controlled by Artaxerxes. Also, see Porten’s & Yardeni’s 2nd volume of Aramaic Idumean ostraca (2016), where they build a chronology of business records they believe dates from Artaxerxes II, III, IV, as well as Alexander IV. See also the Samaria Papyri, where documents are dated to an Artaxerxes (believed to be II & III) as well.

If you are talking about "Fixing the History Books" by Brad Aaronson, which I'm assuming is her brother, I remember that someone on talkreason.org wrote a response called "fixing the mind."

With Lisa, you can find David S Levene's (professor of classics) online.

https://merrimackvalleyhavurah.wordpress.com/2016/06/12/missing-years-in-the-hebrew-calendar/

I actually had a brief email conversation years ago with historian David Levene (mentioned in a previous comment) about Hool's book. His comments:

1. Achashverosh linguistically has to be Xerxes, not Cambyses

2. Thucydides, Aeschylus, Xenophon, Isocrates, Hyperides all make clear that the Persians were not ruling alongside the Greeks but were in fact fighting the Greeks, they make very clear that Alexander the Great did not conquer the Persian Empire from Darius I, but from Darius III

3. We have Athenian archon lists that can also independently verify that chronology (Hool would say they got made up?)

Also kinda funny how Hool's defense of Seder Olam chronology completely invalidates the Kuzari argument, that nations can't falsify their own history